Table of Contents |

To begin with, recall that utilitarianism is the name given to any ethical theory that says something is good if, overall, it brings about utility. If an action brings about utility, then we say that happiness or well-being is the consequence of that action.

You also need to remember that a utilitarian isn’t just concerned with adding up all the good consequences when evaluating an action. They also calculate all the bad consequences as well. This is so they can get a complete account of the utility that an action has by weighing up the good and bad to see what the overall outcome is.

You also need to keep in mind that it isn’t simply about the presence or absence of utility. The degree or quantity of utility is important as well.

IN CONTEXT

Imagine you’re deciding on where to go on holiday. If you decided to go someplace where you could also meet up with some old friends, this would bring about more happiness than if you didn’t. Therefore, the utilitarian will say it’s good.

But if you decided to travel to a place that recently suffered a natural disaster and you volunteer to help survivors, then this brings about even more utility. Therefore, for the utilitarian, this is a better action.

As you can see, there are different degrees of goodness for the utilitarian. The same goes for badness.

EXAMPLE

Avoiding paying your taxes is bad because it reduces the utility experienced by your fellow nationals through the reduction of funding to public services. But if you were a lawyer helping many wealthy people avoid tax, this is worse. That’s because the reduction of revenue is much more severe.Sometimes our everyday understanding of what is right and wrong agrees with what brings about the greatest utility. For instance, most of us think giving to charity is a good thing to do. As long as the charity is successful at helping those in need, utilitarians will also say this is the right thing to do. There are many other similar cases.

EXAMPLE

Many people think that we should buy things responsibly. For instance, we should buy our coffee or bananas from producers that give a fair wage to the people that harvest these products and make sure that their working conditions aren’t dangerous.Assuming the workers' happiness outweighs the consumers' inconvenience, the utilitarian will agree that this is the right thing to do.

There are plenty of cases, however, where utilitarianism says we ought to do things that seem clearly wrong to us. Many of these cases involve intentionally harming someone for the benefit of others.

IN CONTEXT

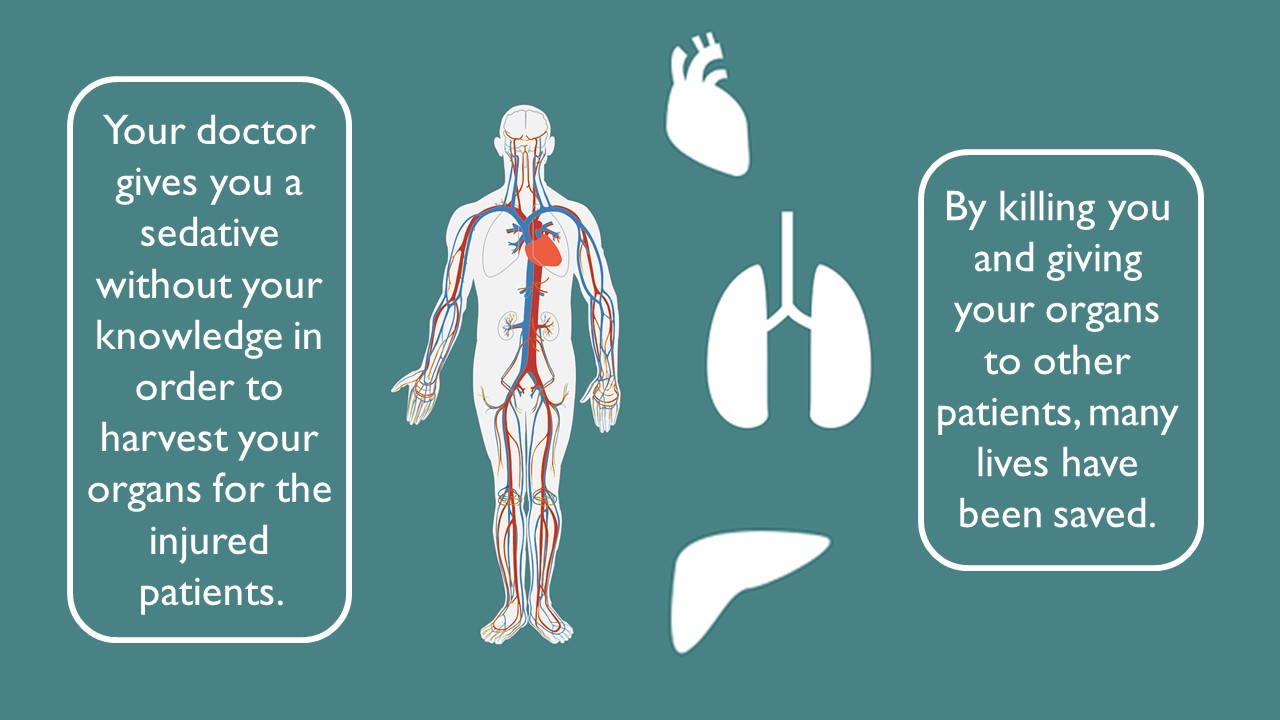

Imagine you go into hospital for a routine check-up. As you’re waiting for your doctor, several people are admitted due to a big car crash. All of them need organs to survive: heart, lungs, liver, etc. There are no organs available for them.

Assuming that saving several lives has greater utility than keeping one person alive, the utilitarian will say that the doctor was right to do what she did.

Most of us would find the doctor’s actions horrific because it goes against our sense of justice. You can think of many similar cases where inflicting harm produces more utility, but at the cost of violating people's rights.

EXAMPLE

Imagine a government of a poor country forcefully sterilizes its citizens so that there will be less hunger, disease, and pain through overcrowding.If this action brings about an overall rise in utility, then the utilitarian will say the government behaved ethically. But taking away people's right to have children without their knowledge or consent seems clearly unethical.

Sometimes it is not clear whether or not our everyday moral views fit with utilitarianism. That’s because a utilitarian can’t always give us clear evaluations of actions due to the difficulty of weighing up utility in different cases.

IN CONTEXT

Imagine you have absolutely nothing but mounting debt.

It’s uncertain whether the utilitarian will say it’s good or bad. That’s because it seems the overall utility stays the same after the identity theft: a wealthy person is now poor, and a poor person is now wealthy.

You find a similar problem when you’re faced with the choice between two kinds of happiness. It can be unclear which you should go for since they seem to both have utility.

EXAMPLE

Imagine you get a lot of pleasure out of eating unhealthy food, but you also want to live a long and healthy life.It’s not clear on the utilitarian account whether the short-term pleasure is better than the long-term benefits.

Philosophers working in ethics often try to apply ethical theories to specific situations. Let’s consider how a utilitarian might apply their ethics to the following issues.

| Utilitarianism and Applied Ethics | |

|---|---|

| Issue | Position |

| Suicide | If there are no benefits of living, only suffering, a utilitarian would say suicide is right because it would increase overall utility. |

| Abortion | If it would result in more happiness for the mother than the potential happiness of the fetus, then it's right. If not, then it's wrong. |

| War | If the suffering and death of soldiers and civilians isn't outweighed by the positive outcomes, then it's wrong. If not, then it's right. |

If you disagree with these ethical judgments, then you may not think utilitarianism is the best ethical framework for judging which actions are right and wrong.

Source: Organ images (modified), public domain, http://bit.ly/2bTAMxT; ID card image, public domain, http://bit.ly/2bTFyf8