When the United States was founded, its leaders formed a government that was radical in some ways—for example, it was led by an elected president rather than a monarch. However, they stopped short of allowing women (or enslaved men, or even white men who didn’t own property) to choose their own representatives. Few leaders or politicians at the time thought that women should participate in politics.

Even without political rights like voting, however, some early American women tried to influence the political process. During the American Revolution in 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, future president John Adams (Adams, n.d.):

Primary Source Excerpt

Type: Letter

Author: Abigail Adams

Date: 1776

... In the new Code of Laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could....

When Abigail Adams warns against placing “unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands,” we get a sense of how much authority men had over their families in the 18th century. But her strongly-worded statement is also a reminder that women have been advocating for their own rights since the earliest days of the United States.

Other, maybe less known, women made similar arguments. In 1791, Judith Sargent Murray’s essay, “On the Equality of the Sexes,” made a case for women’s access to education and the right to control their own earnings. Phillis Wheatly, an enslaved woman living in Massachusetts, published a book of poetry in 1773 where she argued for women’s equality. Her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral was the first published book written by a Black woman in the United States. Though she wrote it while enslaved in the United States, it was published in London. She was freed from slavery shortly after it was published.

For American women, the process of winning suffrage, or the right to vote, took many years. As the U.S. Constitution let the states decide who could vote, 19th-century suffragists pursued a strategy of trying to change the laws in each state. Starting with Wyoming Territory in 1869, a handful of newer states did grant women the right to vote, but overall the suffragists’ progress was painfully slow.

In 1910, Alice Paul and other activists championed a new and more confrontational strategy: try to change the Constitution itself. Departing from their earlier reliance on speeches and publications to gain supporters, the activists increasingly used more aggressive tactics like marches and public protests to make their message known. A final push of activism resulted in the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in 1920, which says that no citizen can be prevented from voting due to their sex.

The success of the women’s suffrage movement was the product of decades of effort by many different women using a variety of tactics. Let’s look at three primary sources: first, excerpts from speeches by two well-known 19th-century activists, and then a photograph of a women’s suffrage protest in 1917.

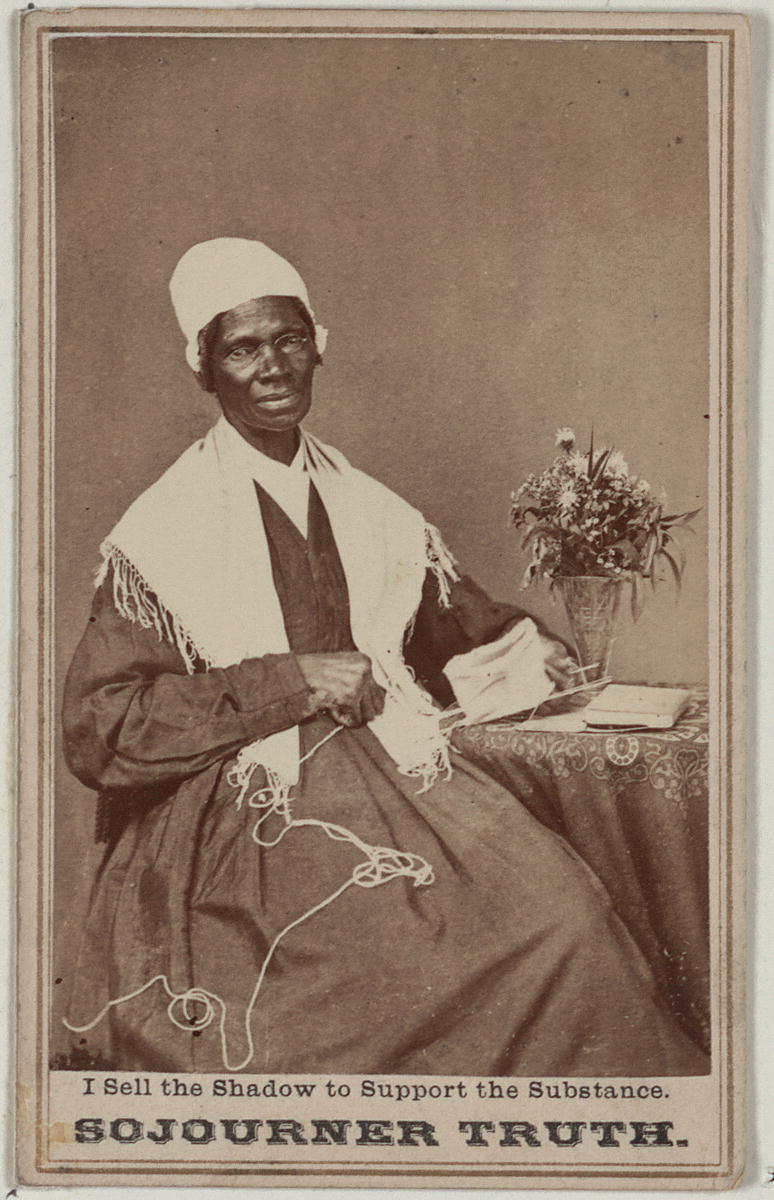

The following excerpt from this speech displays Truth’s characteristic directness and wit (Truth, 1851):

Primary Source Excerpt

Type: Speech

Author: Sojourner Truth

Year: 1851

... I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights [sic]. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am strong as any man that is now.

... The women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.

Suffragists like Anthony faced not only legal obstacles, but also the power of tradition. Political tradition held that only men should choose their political representatives, and cultural tradition held that women should focus on home and family, leaving public life to men.

In 1872, Anthony voted illegally. She was arrested, put on trial, and fined $100. The following year, she gave the speech excerpted below, which shows her problem solving and communication skill (Anthony, 1873):

Primary Source Excerpt

Type: Speech

Author: Susan B. Anthony

Date: 1873

The preamble of the Federal Constitution says:

“We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men.

First, Anthony quotes the opening of the U.S. Constitution, showing that she’s familiar with the political traditions she’s about to challenge. Then she focuses her critical thinking abilities on the Preamble, arguing that women are part of “the whole people” who formed the Union and should therefore have the same rights as men.

Without the right to vote, women had few options for having their voices heard and getting their demands met. Women wrote letters to newspapers in attempts to publish these demands and wrote letters to elected representatives. Too often, though, these efforts fell on deaf ears. In response, women often turned to the streets to express their demands and peacefully fight for their rights.

Now that we’ve examined some of the participants in the women’s suffrage movement and the tactics they use, its time to move forward to the women’s rights movement of the 1960s–1970s.

Source: Strategic Education, Inc. 2020. Learn from the Past, Prepare for the Future.

REFERENCES

Anthony, Susan B. (1873). Women’s Right to Vote. Internet History Sourcebooks Project, Fordham University. sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1873anthony.asp

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 31 March - 5 April 1776. (n.d.). Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society. www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17760331aa

Sojourner Truth. (2020, June 30). U.S. National Park Service. www.nps.gov/people/sojourner-truth.htm

Truth, Sojourner. (1851). Ain't I a Woman?. Teaching Tolerance. www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/texts/aint-i-a-woman