Table of Contents |

In response to a scathing account of the New World environment and its peoples, written by the French scientist George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon during the late 18th century, Thomas Jefferson published the only book he ever wrote: Notes on the State of Virginia.

In his series Natural History, Buffon argued that the continents of the New World emerged more recently from the Biblical Great Flood than the continents of the Old World. For this reason (among others), Buffon concluded that the climate of the New World was more humid and, therefore, more unhealthy in which to live. He went on to suggest that the unhealthy New World environment explained the inferior living conditions of Native Americans.

Jefferson was outraged by Buffon’s argument. Buffon was wrong, Jefferson wrote, and he went on to provide a sympathetic interpretation of European/Native American relations. Jefferson believed that the differences between Native Americans and Europeans was “not a difference of nature, but of circumstance.” He admitted that many native tribes existed in a hunting and gathering stage of development, but he was optimistic that they were capable of attaining levels of civilization similar to Europeans.

Jefferson believed that native tribes required only the proper tools associated with civilization, namely education and private property ownership. Nature would take its course from there. Western settlement by Americans (facilitated by Jefferson’s land ordinances) would surround the Native Americans, and ultimately pressure the tribes to assimilate by acquiring private property, adopting modern farming techniques, and taking part in the market economy.

Despite Jefferson’s optimism, he never took into account the costs involved with assimilation, namely the destruction of distinct and unique Native American cultures that often accompanied frontier settlement.

Frontier settlement during the late 18th and early 19th centuries did not promote the benevolent process of Native American assimilation that Jefferson originally envisioned.

In many cases, violence between settlers and Native Americans contributed to the development of views toward Native American cultures that were quite different from those held by Jefferson.

In 1763, a young boy named Tom Quick saw his father shot and scalped by a Delaware tribal member on the Pennsylvania frontier. The event transformed his life as well as his perception toward Native Americans. "The blood of the whole Indian race is not sufficient to atone for the blood of my father," he reportedly declared, and he promised to kill 100 Delaware individuals before he died. By 1795, when he died of smallpox, he had almost fulfilled his goal.

Tom Quick, and other settlers like him, were informed by decades of violence on the frontier. From their perspective, such conflict highlighted the savagery of Native Americans, and they believed that peace could only be achieved through their extermination.

Images such as the one above, along with stories of frontier violence, were circulated and reprinted widely throughout the United States during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They portrayed American settlers as victims of Native American aggression and implied that Native Americans were incapable of achieving civilization.

In addition to persistent violence, the processes of frontier settlement that Jefferson believed would encourage Native American assimilation worked to disrupt native lifeways, as Chief Sharitarish of the Pawnees noted to President James Monroe in 1822.

By the early 1820s, the Pawnees lived on the Great Plains west of the Mississippi River. Relatively few White Americans lived west of the Mississippi during this time, but the Pawnees and other Plains tribes certainly interacted with White traders, hunters, and diplomats. Such interactions often had disruptive or detrimental consequences, as Sharitarish told President Monroe in 1822:

Chief Sharitarish of the Pawnees

“The Great Spirit made us all — he made us all — he made my skin red, and yours white; he placed us on this earth, and intended that we should live differently from each other.

He made the whites to cultivate the earth, and feed on domestic animals; but he made us, red skins, to rove through the uncultivated woods and plains; to feed on wild animals; and to dress with their skins. He also intended that we should go to war—to take scalps—steal horses from and triumph over our enemies—cultivate peace at home, and promote the happiness of each other.”

Sharitarish went on to describe how trade with White Americans had affected his people:

“There was a time when we did not know the whites—our wants were then fewer than they are now. They were always within our control—we had then seen nothing which we could not get. Before our intercourse with the whites, who have caused such a destruction in our game, we could lie down to sleep, and when we awoke we would find the buffalo feeding around our camp—but now we are killing them for their skins, and feeding the wolves with their flesh, to make our children cry over their bones.”

Sharitarish’s speech to President Monroe provides a first-hand account of how interactions with White Americans had disrupted native lifeways. The Pawnees lived in villages situated along rivers and creeks and, traditionally, hunting bison supplemented Pawnee agriculture. However, Sharitarish’s words suggest that the trading of bison skins with White people had prompted many Pawnees to adopt a nomadic way of life that centered on hunting bison.

Sharitarish’s speech provides evidence that Native American tribes throughout the United States clung to their traditions as they tried to adapt in the face of frontier settlement and trade. By the 1820s and 1830s, however, some tribes in the southeastern United States—the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole—had begun to assimilate in the manner which Thomas Jefferson had hoped.

By the mid-1800s, these peoples practiced agriculture and animal husbandry in ways similar to their White neighbors. They also possessed significant landholdings in much of the South.

The success of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia was particularly significant. The federal government had promoted commerce with the Cherokees since the 1790s and, by 1815, it subsidized Christian missionaries to establish schools within Cherokee territory. More centralized and formalized educational and political institutions emerged. By 1825, the Cherokees adopted the syllabary and, in 1827, developed a written constitution.

This was the context in which Andrew Jackson, himself a frontier settler and slave owner, assumed the presidency following the election of 1828. White people in Georgia bitterly resented the presence of the Cherokee Nation, believing that the emergence of the Cherokees as a viable economic and political entity infringed upon White American development.

In his first message to Congress, Jackson proclaimed that Native American groups such as the Cherokees, who lived within the states as sovereign entities, presented a major problem for state sovereignty. In a subsequent message on behalf of what became known as the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Jackson made it clear that the federal government would no longer protect the Cherokees and other southeastern tribes in their current locations. He also indicated that if the tribes chose to remain in the South, they would be subject to state laws and customs, including those pertaining to race.

Under such a situation in Georgia, a Cherokee man would have fallen under the same racial category as an African American, meaning he would have been unable to vote, own property, testify against a White person, or obtain credit.

In his message to Congress, Jackson supported the Indian Removal Act as beneficial to the region by allowing the southeastern United States to "advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power." Moreover, he asked, "What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12 million happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization and religion?"

Furthermore, individuals who represented southern slave-owning interests in Congress clearly recognized the relationship between Native American removal and the expansion of slavery in the South.

EXAMPLE

In the House of Representatives, members from southern slave states voted 61 to 15 in favor of the Indian Removal Act. Historian Daniel Walker Howe points out that the act would not have passed Congress without the Three-Fifths Compromise, which inflated slaveholders' political influence in Congress.Following the passage of the Indian Removal Act, members of the Cherokee Nation petitioned Congress to state their opposition. Such petitions described a situation in which the Cherokees now lived “as outlaws in their native land” and pleaded with the federal government to uphold its treaty obligations:

The Cherokee Nation, Petition to Congress

“….We are not willing to remove; and if we could be brought to this extremity, it would be, not by argument, not because our judgment was satisfied, not because our condition will be improved—but only because we cannot endure to be deprived of our national and individual rights, and subjected to a process of intolerable oppression.

We wish to remain on the land of our fathers. We have a perfect and original right to claim this, without interruption or molestation. The treaties with us, and laws of the United States made in pursuance of treaties, guaranty our residence, and our privileges, and secure us against intruders. Our only request is that these treaties may be fulfilled, and these laws executed.”

The Cherokees also sought assistance within the federal courts by arguing that the state of Georgia was ignoring their rights guaranteed by federal treaties. In his ruling of Worcester v. Georgia (1832), Supreme Court justice John Marshall vindicated the Cherokees' cause by arguing that the Cherokees and other Native American nations had distinct identities that were protected by federal treaties.

President Jackson ignored Marshall’s ruling. He reportedly said, "John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it," and the pressure for Native American removal persisted.

After several years of legal wrangling, the Cherokees were among the last tribes removed from the southeastern United States. During the winter of 1838-1839, the federal military gathered 18,000 Cherokee men, women, and children into stockades and then forced them westward toward an area in modern-day Oklahoma. Approximately 4,500 individuals died along the Trail of Tears, as the route from Georgia to this territory came to be called.

Additional Resources

View primary sources and learn more about the history of Cherokee Removal at the Smithsonian Institute.

In 1776, when the United States declared independence, Native Americans were present throughout eastern North America. Yet, by the 1840s, the majority of White Americans viewed Native Americans as an inferior, bygone relic of a past era. Frontier violence and desires for indigenous lands certainly contributed to Native America removal. Removal also represented a manifestation of White supremacy or the assumption that White American culture was superior to Native American cultures.

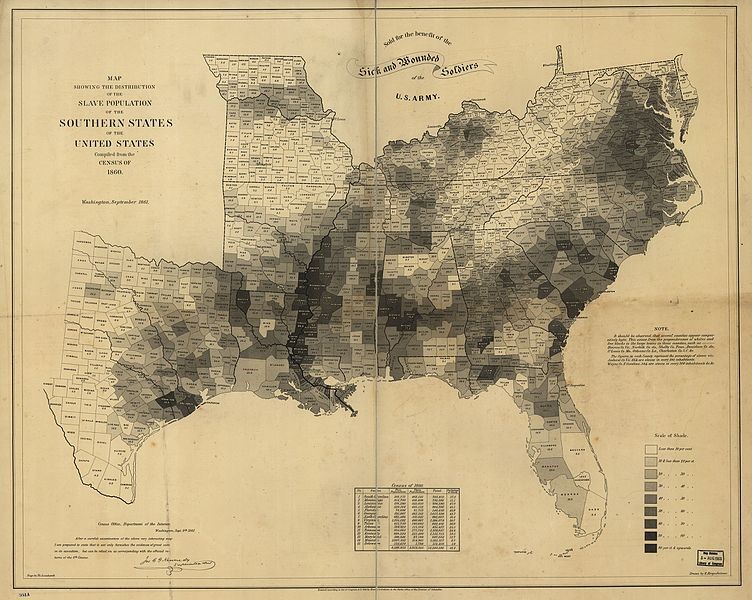

The removal of the Cherokees and other native tribes from the southern United States also contributed to the expansion of racial slavery throughout the region, as the map below shows:

The map shows that places such as the Chesapeake region (Virginia and Maryland) and South Carolina continued to have high concentrations of African American enslaved people. This should not come as a surprise, because both regions had been at the center of American slavery since the colonial period. Of particular note here, however, is the expansion of slavery across the southeastern United States and into the Mississippi River Valley. In 1800, much of this territory was controlled by Native American tribes. By 1860, though, slavery and cotton cultivation was firmly established throughout the region.

Source: This tutorial curated and/or authored by Matthew Pearce, Ph.D with content adapted from Openstax “U.S. History”. access for free at openstax.org/details/books/us-history LICENSE: CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION 4.0 INTERNATIONAL

REFERENCES

Jackson, A. (1830). Transcript of ‘On Indian Removal'. Ret Jan 20, 2017, from bit.ly/2kGpWPE

Howe, H. “Heroism of a Pioneer Woman, 1860.”Newberry Call Number: f 89.418. Newberry Digital Collections. http://bit.ly/2l24w2X.

Chief Sharitarish Speech to James Monroe & Appeal of the Cherokee Nation both republished in Foner, E. (2014). Voices of freedom: a documentary history. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.